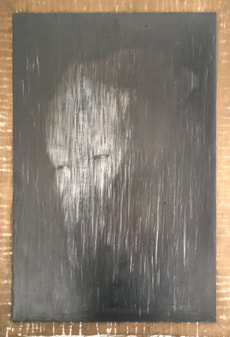

Blind Mirrors

Committed to the physicality of creation, to making and taking yourself out of the frame. Perhaps it is, in fact, only your image we see in these mirrors, asking you to look at yourself as a drawing, as something you create. Are we capable of rubbing ourselves out and beginning again?

[Extract from critique, see below]

|

Double Portrait triptych 2002 (graphite powder, wax, acrylic, gilt, paper, on MDF; each panel 120 x 83 cm). Based on Van Eyck's 'Arnolfini Marriage'.

|

|

|

Mirrors that Hide; Mirrors that Simplify

Piece written by Jenny Allan (RCA) 2001 A reposing graphite glove greets us. Significantly, the hand that organised this space leaves its protection at the entrance. This placid aching glove, languishing in the absence of the hand that drove it, emptied of purpose, conscious of being transformed by creativity, remade in the name of art. Walking into the space you come face to face with a series of hand-mirror sculptures hanging on the wall, which immediately disarms you. You feel a presence from behind. A pressure, the compact fluidity of a graphite-covered wall: a smoke screen, the sea at night or a night sea. This wall drawing seems to act like a dense network, a mesh of movements, which make up its creation: a compressed completeness. The wall looks at its reflection across the space. A drawing that has never seen itself before. I look at the mirrors and I become the graphite wall, I am drawn: making myself up. We are mirrored in our creations, where we find our true reflections. What do we see when we look in our lives: ourselves in those lives? A mirror is a web that traps our image, these blind mirrors free us, because in reality we are inseparable from our reflection. 'Did you see the mirror by the filing cabinet?' said Nicole. . . ‘It’s from Belgrade, very old. So old that it doesn’t work properly’. 'What do you mean?’ 'Sometimes it is slow to work. Like an old wireless. It takes time to warm up. Come I’ll show you.’ They walked around the filing cabinet and stood to one side of the mirror. ‘Usually it works normally. Sometimes not. We’ll see.’ Nicole took Luke’s hand and they moved in front of the mirror which, for a second, showed only the bed. Then their reflections moved inside the frame and looked back at them. They stepped aside but, for a few moments, the mirror continued to hold their images . . .[1] There is no reflected delay from June’s mirrors: the delay is eternal. These are mirror portraits of an unrecognisable self: an unlikeness. Mirror sculptures that allow us to imagine a reflection, to choose ourselves, enabling our different faces that exist in divergent roles to align. We don’t escape ourselves when we shut our eyes, we just escape the revelation of reflection; looking at these mirrors is like seeing with your eyes shut. Mirrors that hide; mirrors that simplify. Mirrors whose very make-up holds the potential to draw me. Pushing me back onto and into myself, to consider my own accuracy. A repetition that reiterates and denies the gaze that doubles. A resemblance in disguise: [. . .]the mirror is saying nothing that has already been said before . . . this mirror cuts straight though the whole field of representation, ignoring all it might apprehend within that field, and restores visibility to that which resides outside all view. But the invisibility that it overcomes in this way is not the invisibility of what is hidden: it does not make its way around any obstacle, it is not distorting any perspective, it is addressing itself to what is invisible…’[2] Is truth visual? As artists we make things up every day, create images that don’t exist as true or false, but perform an authentic misleading. Absent reflection, absent hand; the glove reveals your struggle. Your effort to create the graphite wall is part of the work, and lies undisturbed in the presence of the glove – that expended energy – the unseen element. Committed to the physicality of creation, to making and taking yourself out of the frame. Perhaps it is, in fact, only your image we see in these mirrors, asking you to look at yourself as a drawing, as something you create. Are we capable of rubbing ourselves out and beginning again? [1] Geoff Dyer, Paris Trance, p. 74, Abacus, 1998 [2] Michel Foucault ‘Las Meninas’, in The Continental Aesthetics Reader, edited by Clive Cazeaux, p. 404, Routledge 2000 |